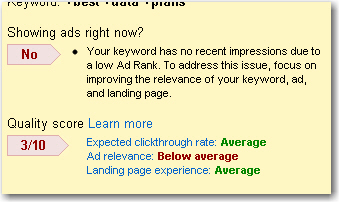

Unlike the average American 15-year-old, AdWords advertisers now have definitive proof that they can’t all be above average. This comes in the form of Google’s new breakdown format for keyword quality score reporting, by Expected CTR, Ad Creative, and Landing Page Quality.

Most advertisers already know that Quality Score (which determines ad rank and eligibility in the auction, and ultimately, heavily influences CPC’s and ROI) derives from CTR and “other relevancy factors.” This new disclosure shows that Google continues to refine the formula to help some advertisers get their “fair rank,” and to deter others from showing ads. They’re doing this by incorporating more and more data about ad creative and landing page quality. Today, Jonathan Alferness, Director, Product Management, on Google’s ads quality team, reminded me that these particular factors have been increasingly involved since a major round of updates in 2011. Thus, the additional disclosure at this stage is a way of giving advertisers some useful insight on top of an aggregate score number like 4 or 7.

When this disclosure was announced on April 24, there weren’t many insightful comments around the industry, with the unsurprising exception of George Michie, who as you can see from his post was roughly over the moon about the new info.

I wasn’t completely sure I understood the exact implications of the new reporting, so today I finally caught up with Jonathan to get the Googler’s deeper dive on what the headings mean.

Expected CTR is a measure of your CTR relative to other advertisers you’ll be duking it out with over the same keyword queries. If it’s below average, you’re probably targeting more broadly than others are in the auctions you will be entering against other advertisers, so you may be willing to accept a lower ROI (or bid lower, for less volume). If it’s above average, it’s quite possible that your ROI here will be benefiting from pursuing a strategy of granularity in your account structure (for example). This one has been the core of the Quality Score formula for years, but the additional disclosure is a helpful reminder that the measure is relative. You will do OK on some keywords even if your CTR looks low on an absolute basis, as long as you’re doing as well as other advertisers are. For some queries, consumers simply aren’t in the mood to click on ads. But Google will still show some ads.

Ad relevance, according to the loose description given to me by Jonathan Alferness, measures “how well the creative matches the keyword.” So what does this mean, exactly? How does Google determine this? They can’t and won’t disclose the secret sauce, but examples can help. What if there is nothing wrong with an ad, and users didn’t seem particularly dissatisfied or misled by it, but they weren’t all that likely to click on ads in that particular keyword space in general? Google wants to refine the process to rescue such keywords from “low Quality Score hell,” (my words, not Google’s) so that despite low CTR’s, advertisers may continue to serve ads despite a certain pattern of user response that does not scream “I’m buying today”. The ad is relevant and the ad does not bother people.

Some ad creative is in fact annoying to users despite some of its metrics being OK from the standpoint of the keyword CTR as well as the post-click engagement numbers. I still have trouble understanding how an ad could be deemed less relevant than it ought to be (below average), while the expected CTR numbers *and* the landing page quality numbers come in as average… unless Google has decided that something called ad relevance is intrinsically a good thing separate from both CTR’s and post-click engagement numbers like bounce rates and other elements of poor user experiences that cannot be measured with (eg.) bounce rates alone. Google may be willing to down-rank or show less often ads that are in some sense ‘problem ads’ or ‘spammy ads’ even if they do not get flagged as such by other more conventional measures of spamminess. Too many ads from Mars when the searcher is from Venus leads to an overall feeling of clutter on the page. Shining up the ‘Quality’ of the ads portion of the search results page overall could be an important part of maintaining user trust not only in any given ad, but importantly, trust and respect that the ads portion is worth looking at and represents a high standard of communications.

In other words, regardless of how it is achieved, Google appears to believe in a higher-order concept of relevance, independent of specific measures like CTR. Obvious means of achieving that might be to simply mirror some of the user’s keywords in body copy, etc. But less obvious might be: users feel funny about getting your brand offer with the brand name in the headline (say), when they have explicitly searched for information about comparison charts, or “best” something. To “spam” them (even slightly), the formula is going to ask you to either pay more, or to alter both your landing page and ad copy. Alter one without altering the other, and you’ll likely be deemed less relevant either way. There is going to be less of a free lunch even when you somehow manage to maintain a decent CTR. And if all advertisers do is change their ad copy slightly to annoy users less, that might be good enough for Google — not necessarily because one ad gets clicked more, but also because minimizing the appearance of some kinds of ads means that the ad space overall gets clicked more and respected more over time.

It could be other things, too. If Google knows and shows you that your Expected CTR is above average, but your ad creative is only average, that could be telling you that Google knows that your CTR will probably go even higher if you take steps to match the ad creative more closely to the actual keyword. You’re doing “well,” (possibly just due to elements like the granularity of your targeting or the appearance of your brand name in the Display URL), but Google knows that the odds are you aren’t doing as well as you could specifically with the ad creative. By trying ads with “instant buffalo wings” specifically in the ad headline for the query “instant buffalo wings” where currently your headline is “hot spicy wings,” you might generate even better user response — primarily in terms of CTR, but possibly in terms of response right through the buying funnel. Does Google benefit? Yes. Will you? Maybe.

Landing page quality: When this is below average, it could mean any number of things, more than I have space to go into here. In any case, this should put to rest the majority of people’s questions about whether their landing page is the source of their Quality Score woes. It either is, or it isn’t, and this new reporting will say as much. It won’t tell you anything about what is wrong, how serious the problem is, etc. But in all cases it will reinforce the point that this game is largely about…

User expectations.

Many have heard of the concept of information scent. This new Quality Score reporting just reinforces the idea that optimizing a PPC account revolves largely around removing that puzzled state that slightly-off advertising gives to a searcher. The more laser-perfect your sequence from keyword query and campaign organization, to ad copy, to landing page, and beyond — in relation to the user’s expectations and intent — the better you do.

Why does Google “get involved” to this degree rather than letting advertisers figure it out? Broadly speaking, it’s to help them learn this process on their own without actually privileging the interests of one advertiser over another. And broadly speaking, it’s to continue to address and weed out any sense of “spamminess” in the ads that stems from situations as benign as advertisers not thinking through different meanings for keywords, throwing too many keywords into an ad group assuming that they are all worth “a try” because the keyword tool said they were popular, etc.

Example: Competitor Words

There are some important specific cases, though, that illustrate the principles acutely. One of the main ones is the common practice (largely legal in most jurisdictions) of showing your ads when a user types a competitor’s name as their search. Think of three common scenarios here:

1. You’re advertising on your own brand name, and using the ad unit (including appropriate extensions) to extend your grip on screen real estate, test specific offers, etc. Here, your expected CTR relative to other advertisers will be way above average. Your ad relevance will also be well above average because you alone have the luxury of using your trademark in ad copy. And your landing page quality will likely be above average as well, because perhaps you are a respected brand name. It should at least be average. Put the three components together, and your Quality Score is often a solid 10/10 and virtually no one can dislodge you from top spot. You may be getting your clicks here for single-digit pennies per.

2. You’re advertising on a competitor’s brand name… and it is not going well. Previously, there was some mystery as to how this process worked. Your CTR might not be terrible, and yet your Quality Score keeps dropping so low that your eligibility is in the toilet and your CPC’s become prohibitive. But relative to the brand, your CTR is definitely not great. And your ad copy isn’t helping, because you don’t have the luxury of including the searcher’s keyword — the competitor’s name — in your ad copy. (It isn’t legal or allowed by Google and/or in most jurisdictions.) Remember, even on top of normal CTR’s, you could be dinged for the intrinsic lack of relevance of such an ad. And finally, users tend to get dissatisfied when they visit landing pages on ads for the other guy’s brand. Not always, but insofar as many users are ticked off, the formula will reflect that, too. That explains why most times, it’s not feasible to advertise on “competitor words,” and why that can all be done algorithmically to embrace far-reaching principles. It’s only a “cash grab” if you’re on the wrong end of it.

3. But sometimes, you can do just fine here. While you may take a slight hit on the ad relevance piece, what if your CTR’s are actually pretty high because your offer was pretty relevant, kind of cool, was thoughtful in challenging the supremacy of the leading brand, pointed to a helpful comparison chart, etc.? What if, furthermore, users actually liked and appreciated the landing page when they arrived? If and only if that’s the case, you might come in with Quality Scores in the 5-7 range, and thus be the exception that proves the rule: advertising on competitor terms is something that you must do with great care.

Has this new disclosure helped me immediately in crafting better ads or weeding out keywords that shouldn’t be there? Not really, for two main reasons: (1) I already think that way, and (2) we’re still watching the ROI data most closely, using Quality Score as a learning tool.

And the new reports are confirming some hunches that I’ve been working with for some time. Since we’ve been doing this a long time, my colleagues and I generally understand when we should expect to pay a premium for overly broad targeting (or overlapping, sadly, with non-commercial intents on ambiguous keywords), and when we’re going to get a bonus for really drilling down and matching very specific keywords to tightly-written ads (thus “above average” expected CTR). The reporting will also provide us with insight as to how Google is working to “rescue” ads if they are above average in relevance; and can remind us when keywords are average or even above average in relation to expected CTR compared with other advertisers, despite the fact that some keywords must toil in an “organic SERP’s are better” keyword universe that most users would rather not click ads for. In short, we now have more insight into whether a keyword is “in a tough space” or whether it’s truly a case of “you suck”.