What do you get if you spend a week pondering life, climbing hills in Italy, watching football, reading Super Freakonomics, and then come home to play around with one of Google’s many incredibly helpful Labs creations?

Garbled conjectures about comparative fertility rates and their possible correlation with soccer victory in this year’s World Cup, perhaps?

The economist and journalist behind Super Freakonomics dazzle us with the way that inquiring economists’ minds work. From correlating television exposure in some regions of India with changing social and marital mores and thus lower birth rates, to the maxim “friends don’t let friends walk drunk,” after you read this book (sequel, of course, to the blockbuster bestseller Freakonomics), your mind may never work the same again.

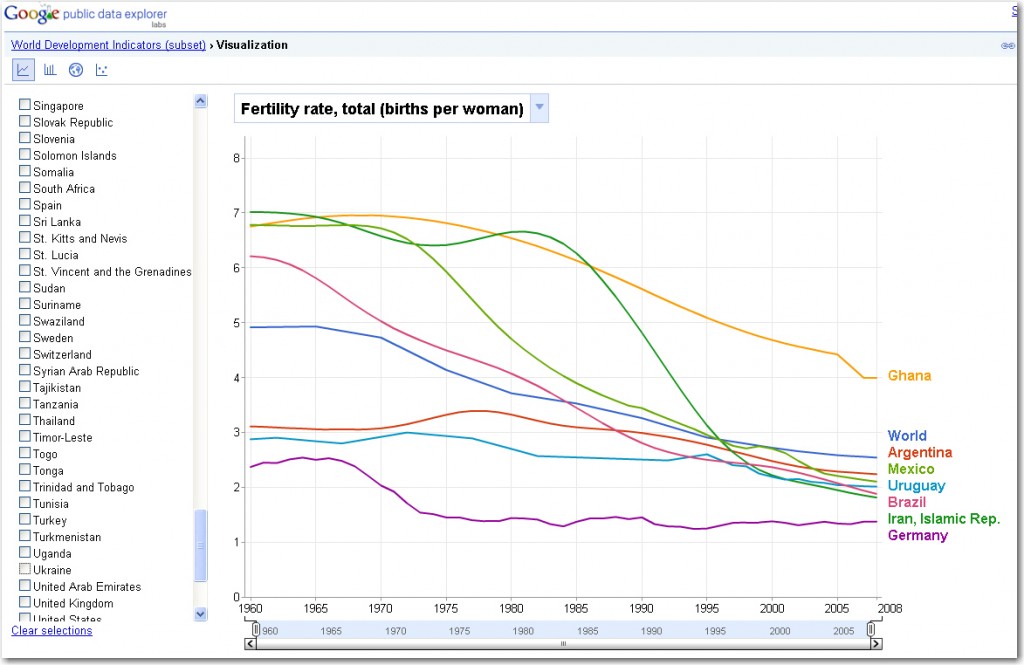

(On interesting conjectures about birth rates, on a previous day off, I had the chance to go through a Mother Jones issue with a focus on global population issues. One of the highlights was the remarkable coordinated campaign in Iran to change cultural perceptions related to birth rates. It’s one of the most dramatic examples, globally, with a steep plunge in birth rates in a decade’s time; some scholars call it “the Iranian miracle”. Mexico’s graph is straighter and the decline more spread out in time, but oddly similar in its before and after outcome; in a completely different way, Russia’s and Ukraine’s graphs since 1960 show them to be nearly identical, well below 2.0 nearly the entire time, as if they were essentially the same country with identical cultural norms and family practices.)

The Freakonomists are wrong to say that thinking this way is the purview of “economists,” however. Slyly, the most brilliant thoughts in the book are routinely attributed to tenured stalwarts of “behavioral economics” toiling in “official” positions in accredited university economics departments.

That’s misleading. All social scientists can and do look for interesting patterns in data and behavior — even if economists shoehorn in the concept of “incentives” to stay on message while essentially exploring the same patterns as anyone else. (Incentives are indeed important; economists seem to imply that they have a monopoly on fully understanding their importance.)

More importantly, insofar as any educated person now has access to data sets (though, to be sure, not all the required training and statistics background to make sense of it), the parlor game of looking at patterns in human behavior is open to a much wider group of people. Call it the pro-am movement in data interpretation.

Google is already well known for their mission statement (“to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible”), and for some very concrete efforts to put more actionable data at people’s fingertips; in particular, Google Analytics.

But they’re certainly not stopping there. Let’s hope they apply the same persistence and spirit of openness to other socially useful data sets.

As they do this, they’re going to give the emerging “brand name for structuring data” — Wolfram Alpha — a run for its money. Google can do that, as can any leader. If Wolfram Alpha innovates, Google can cherrypick the most useful ideas, and repackage them for a mass audience.

Ask any rank and file professor what she thinks of the Google Public Data creation in Google Labs, and you’ll no doubt hear squeals of delight. You would hope, too, that some students would actually cause their professors to squeal with delight (and maybe dole out “A’s”) by taking the bull by the horns and using this data in their work — just out of sheer interest. Some profs will no doubt be surprised that it’s this easy to slice and dice the data. Students are typically reluctant to learn how to do research in proprietary databases. By contrast, this makes it easy and fun.

So as a non-student, I get to focus on “fun”. Poring over the “country by country fertility rates” graph, I thought to myself — what if I plug in a few of the remaining World Cup soccer nations? Compare them with the losers? Any patterns?

I guess we won’t know until the tournament is over.

What we do know is that so far, a psychic octopus has a 100% success rate in predicting Germany’s game outcomes in the World Cup.

Thus far, it seems like we’re heading for a potential scenario where fertility rates (unlike octopus intuition) bear no relationship to soccer game outcomes in tournament battles for global supremacy… but further research will be warranted if Ghana, with the highest fertility rate amongst remaining World Cup nations — goes all the way. The situation will be a bit more confusing if it’s one of Japan, Slovakia, Portugal, or Germany: all have very low fertility rates.

An enterprising Super Freakonomist (or Amateur Datacologist) would then be forced to turn to a more specific possible fertility correlation with soccer success: the fertility rates of the players’ wives. And/or girlfriends.

Other possible correlates of winning at football could include hair length, foot speed, prevalence of left-handedness, how well paid (over or under the table) the players are, caloric intake, hours of sleep, foot size, and GMAT scores. I like that Google has big computers, because I think we’re going to need them.

Maybe the moral of the story should be: friends don’t let friends blog drunk.

Which, if I had a team to cheer for, I probably would be. Luckily, I’m a fourth-generation Canadian (current fertility rate: 1.6).

Or maybe I should take a cue from the Italians. After Italy bowed out of the tournament, everyone in Rome began feverishly cheering for the United States because the game was on TV and it seemed like the thing to do. Suddenly, American, French, and British tourists bonded with Italy natives (loudly) over pints of Irish beer, as the crowds watching the game against Ghana spilled into the streets. When Ghana prevailed, however, all this was forgotten, and everyone partied all night long to salute their new heroes. When in Rome.